Guest blog post by Laura Lorenz, PhD, MEd and Diana Weggler, Photovoice Worldwide

Since 1992, Photovoice has been used by people all over the world as an action research tool to create positive change. A participatory visual approach using photographs and captions, Photovoice creates opportunities for people with valuable lived experience—referred to as co-researchers or co-creators—to have a voice in the decisions that affect their health, lives, and communities.

Sexual violence prevention staff have key facilitation skills and an understanding of the power inherent in the Photovoice method. That said, some forethought will help get you started with planning your project. Here are some key issues related to power, consent, and safety to consider before undertaking a Photovoice project in your sexual violence prevention work, along with some best practices and tips for success.

1. How can we use Photovoice to share power with co-researchers and community partners?

Co-researchers need to be involved in decision making throughout the project. Together, at the start of your project, brainstorm a list of community partners—decision makers, community leaders, and anyone else who might be invested in the project. Consider engaging partners before the project begins. Can they come to a project session, host a field trip, provide expertise, or host an exhibit?

Best practice:

- Create an advisory group that can identify partners, outreach opportunities, and solutions throughout the project. Ideas and connections will emerge, resulting in new and different ways to achieve action or reach important audiences with your project.

Tip: Identify a framework that values sharing power with people who have been excluded from decision making roles in the past and use that framework to guide your advisory group.

2. How do we plan for consent and safety throughout the project?

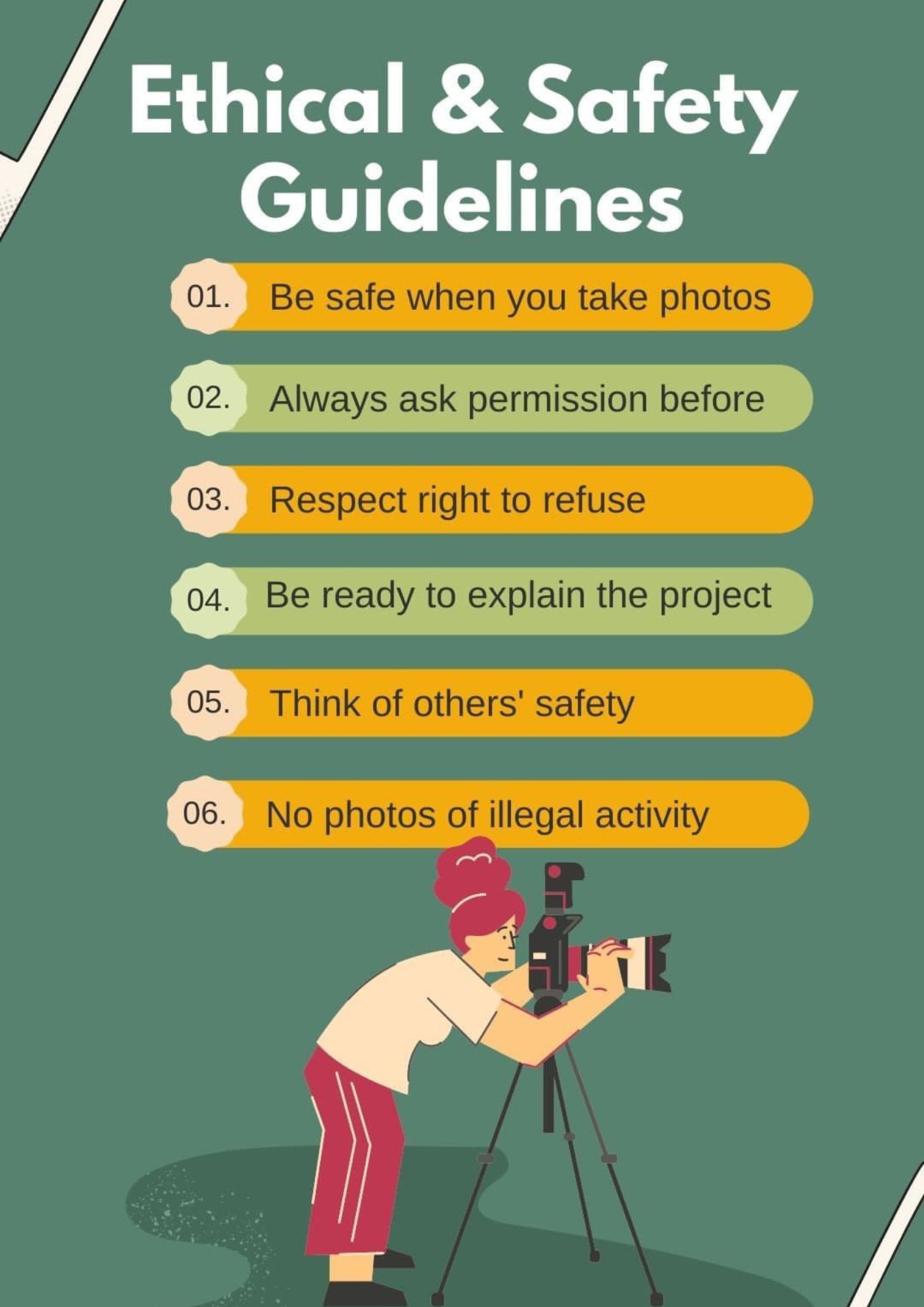

Planning for consent and safety begins well before your project starts. Discuss options for photo consent with your advisory group, which should include those that are most impacted by the issue. Develop a process for informed consent to make sure that any person shown in a project photo understands the goals of the project and has given consent to have their photo taken. You also need consent from co-researchers and possibly their parents or guardians before sharing any photo outside the group - for example, in an exhibit or online.

Prioritize both physical and emotional safety. Taking photos and discussing them can bring up both positive and negative thoughts and memories for participants. Identify trauma-informed strategies to create a safe space for sharing emotions and experiences during photo discussion sessions. Consider asking co-researchers to make drawings or art that share something positive (or negative) about the project topic or their community before taking photos, and then determine photo ideas based on the discussion.

Best practices:

- Provide opportunities for co-creators to practice Photovoice conversations with community members to explain the project, why they are taking photos, how the photos will be used, and answer any questions. Being prepared to explain the project will help co-researchers stay safe and help community members feel respected.

- In the project’s photo consent forms, include plain language that explains the project and its activities and goals. This will help parents or guardians make informed decisions about consenting to have their minor child or ward share a photo in an exhibit.

Tip: Read about these topics and more in the OAESV Photovoice Toolkit.

3. How do we ensure ethical data collection and social inclusion in our topic selection and Photovoice process?

While your work on sexual violence prevention may have a specific topic in mind before your Photovoice project begins, true action research and ethical data collection means deciding on a topic and photo-taking questions together with your co-creators. What are they most interested in exploring? What aspects of their lives and communities do they want to share?

Social inclusion in Photovoice means collecting data from those who are systematically under-resourced and therefore “under-heard.” In SIDEWALKS to Sexual Violence Prevention: A guide to exploring social inclusion with adults with developmental & intellectual disabilities, Cierra Olivia Thomas-Williams, M.A. writes, “Inclusion cannot be achieved without data on and the perspectives of those who are ‘left out’, since a society that is inclusive of the ‘least of us’ will be one that fosters the lives of everyone.”

Best Practices:

- Providing a safe and inclusive space for co-creators is an integral part of Photovoice. They will determine what that looks like; for example, are there any intellectual, physical, socio-economic, cultural, gender, language, or other differences within the group that need to be bridged? Be ready to enter into projects with no preconceptions and learn how to confront your biases. Adopting an anti-oppressive approach from the start will ensure everyone feels included and has an opportunity to participate equally.

- Using arts-based methods to work with photos and captions creates opportunities to communicate in innovative and inclusive ways, and helps level differences in abilities, education, training, and experiences.

Tip: Using a health equity approach can help put the rights and values of community members at the center of your work.

4. How can we engage co-creators in developing shared ideas for success with our Photovoice project?

Brainstorm with your group about how they define success with Photovoice. Consider using the social-ecological model to envision success at different levels, from individual to interpersonal, organizational, and community/societal. Consider this discussion question: What changes would you like to see in your friends, classmates, and peers after this Photovoice project? Possible answers may be: Feeling less alone, feeling empowered, feeling safe.

The learning process doesn’t stop when the project ends, and shared ideas for success may evolve over time. Promote mutual learning and continued dialogue on opportunities for positive change by incorporating interactive components such as roundtable discussions or brainstorming sessions into exhibits and other outreach.

Best practices:

- Once you have defined success, identify and implement ways to know whether you have been successful or not. Examples could include: a post-exhibit survey to explore whether attitudes or awareness has changed, or post-exhibit surveys to explore commitment to change.

- If of interest to co-researchers and community partners, consider developing multiple sharing opportunities to aim for different types of success (e.g., exhibits, videos, events, trainings).

Tip: Gain ideas for evaluating and measuring success with Photovoice by visiting NSVRC’s Evaluation Toolkit.

A Note from Team NSVRC:

Listen to our Resource on the Go podcast episode: Prevention Gets Visual to hear more about the collaborative work between programs in Ohio and Photovoice Worldwide to create their Photovoice Toolkit.

For further learning on Photovoice —including blog posts, community webinars, workshops, trainings, and consulting—visit www.photovoiceworldwide.com.

About the Authors:

Laura Lorenz, PhD, MEd: Laura discovered Photovoice in 2000 while exploring arts-based approaches to youth programming and civic engagement for a Master of Education in Instructional Design. Laura has led Photovoice trainings for medical schools, professional societies, community funding organizations, and government agencies, and offered photovoice professional development trainings for clinicians, researchers, educators, students, nonprofit staff, and managers. In 2018, she launched the online course “Talking with Pictures: Photovoice” through the University of Hawaii at Manoa’s Outreach College and Center on Disability Studies, and in 2019 co-founded PhotovoiceWorldwide.

Diana Weggler: Diana joined the PhotovoiceWorldwide team in 2020 as a content editor and proofreader. Involved in writing for and editing print publications since childhood, she has made word-smithing her professional career for more than 20 years. In addition, she spent 10 years as the senior speechwriter for the president of a small, liberal arts university in New England. Educated at Cornell University, Diana holds a BA in English. When she is not knitting, she is the volunteer Board director of The Veterans’ Place, Inc., a Vermont nonprofit that provides transitional housing and programs for homeless Veterans.