|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The focus on campus sexual assault in recent years stems from the work of student activists and victims who have spoken out about the issue, attracting media attention and prompting federal and state legislation and guidance for more effective efforts at prevention and response. As a result, SARTs have become more involved with college and university settings.

First-time SARTs have formed on some campuses; in other areas, some established SARTs have invited campus representatives to join an existing team. The development or expansion of SARTs that have a campus focus strengthens support for victims and bolsters preventive measures.

This section of the SART Toolkit provides information on campus sexual assault. Every campus is unique; the information in the SART Toolkit is presented as general information to guide SARTs that seek to become more familiar with school settings, and for campuses seeking to enhance or expand their services.

Select a section of the SART Toolkit for additional information on:

Any SART that considers working with a campus will benefit from understanding the history of anti-sexual assault efforts on that campus. SARTs may find they are joining forces with a campus that has a rich history of violence prevention efforts.

The campus anti-violence movement was born in the 1970s alongside the rape crisis movement. How campuses addressed sexual assault — and where services and prevention efforts were housed — varied widely from women’s centers to student health services. Although some may believe the recent focus on campus sexual assault is new, many college campuses have long-standing rape prevention education and response programs. For these schools and personnel, hearing of a “new epidemic of campus sexual violence” may be frustrating as neither SARTs, community agencies, nor upper-level administrators may realize that some campuses have worked on this issue for decades.

Sharon Davie’s book, University and College Women’s Centers: A Journey Toward Equity, provides a history of the Women’s Center and Rape Prevention Education movement on campus. [312]

Many campuses have fortified their campus prevention and response efforts after receiving grants from the DOJ, OVW Campus Grant Program. Since 2007, OVW has made yearly grants available to approximately 30 campuses. The grant requirements have sparked change. For example, many OVW grantees were compelled to develop a coordinated community response (CCR) team, which consists of departmental representatives from across campus as well as community partners. Due to participation in the program, institutions that have received campus grants may have more developed prevention and response efforts.

Consider these statistics on the prevalence of sexual assault on campus:

The American Association of Universities (AAU) has aggregated data from its campus climate survey. Conducted on 27 different campuses, the survey has yielded some of the most current and detailed information available on campus sexual assault. Among the AAU’s findings were the following: [317]

Men, individuals with disabilities, members of cultural and religious minority groups, LGBTQ individuals, and international students also experience sexual assault on campus, and frequently do not report their victimization. In response, institutions of higher education and victim service professionals that serve campus communities can seek to ensure that their outreach, services, and policies reflect the composition of their campus community, enabling them to respond to the needs of a wide range of victims.

According to data from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, as of March 2016, more than 1.3 million foreign students were pursuing studies in the United States. The Institute of International Education states that enrollment of international students in the United States has been growing, with a 7 percent increase between the 2014–2015 school year and the 2015–2016 school year alone, when the total enrollment topped 1 million students for the first time. [318]

Seven of the top 10 countries of origin for international students in the 2015–2016 school year were in Asia. Sixty percent of international students come from the top four countries: China, India, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea. [319]

According to the U.S. Department of Education, Title IX protects all students regardless of national origin, immigration status, or citizenship status. [320]

International students studying in the United States fall under one of several categories:

International students may experience quid pro quo sexual harassment from instructors and employers, intimate partner violence (IPV), and acquaintance sexual assault, just as their native-born counterparts do. However, international students (especially female students) may be at risk for sexual victimization due to vulnerabilities involved in studying abroad, such as living away from their family support system, residing with unfamiliar people, and living under student/instructor and student/employer power imbalances.

Marginalization due to sexism, racism, and cultural mistrust may make it difficult for international students to report victimization. [322]

Campus prevention efforts, campus SARTs, and community SARTs that include campuses or partner with campuses can help to ensure that international students are aware of U.S. laws and services related to sexual assault. Due to language barriers and unfamiliarity with institutional procedures, students may not be aware of the on-campus resources available to assist them following an assault.

Prevention efforts and information may need to be adapted to be culturally relevant and accessible to international students, including providing information in the student’s native language and providing follow-up information beyond initial orientation. Increasing awareness of the way culture shapes sexual norms will assist campuses and communities in providing culturally responsive information to international students.

A number of campus communities and supporting organizations are striving to include outreach and information for international students regarding sexual assault. The University of New Hampshire offers a website specific to international students’ rights and common questions about seeking support for or reporting sexual assault on campus. International Student Insurance has developed an informational video, Sexual Assault Awareness for International Students, about sexual assault, consent, and reporting in the United States. The University of Albany has developed a brochure on Responding to Sexual Assault for International Students.

Following the trauma of sexual assault, students can have difficulty continuing their studies. However, taking a break from school may not be a simple option, since full-time enrollment is a requirement for international students to maintain valid student visa status. Campus SARTs can work with administrators and faculty to help international students who are having academic difficulties navigate their options.

Case Example:

A female university student reached out to Central Pacific Asian Family Services when her husband sexually assaulted her after she gave birth to their one-month-old baby. She had endured previous abuse because she was living under “his roof” with his parents. She was on a student visa. Although she experienced the trauma of both sexual assault and intimate partner violence (IPV), she was not aware of the options available to her. When she fled for her safety, she had to drop out of her program because she could not return to the university that her husband also attended.

As an immigrant victim of sexual assault, she needed services beyond the sexual assault forensic exam and subsequent criminal justice process. In this case, the SART helped her access other resources, such as shelter and legal support for her immigration status in order to thrive as both a student and a mother.

Ideally, those assisting international students following an assault will assist the victim in identifying and accessing appropriate and supportive campus resources, including those that are specifically intended to assist international students with visas. For more information, see Foreign Student Victims of Sexual Assault.

Since 2010, the national spotlight on sexual assault activism and cases on campus has prompted increased awareness of the crime and greater accountability for campuses and offenders. As an investigative series, The Center for Public Integrity in 2010 conducted the first large-scale media report on campus sexual assault. [323] Since then, major media outlets such as the New York Times have published pieces (“College Groups Connect to Fight Sexual Assault”) that are credited with highlighting student activist efforts and connecting students in ways that have furthered the movement. [324] Higher education journals, such as the Chronicle of Higher Education, have also published major pieces on the topic. [325] Media attention to sexual assault on campus has prompted state and federal efforts to address the issue.

Some state legislators have taken issue with campus adjudication proceedings, calling them “kangaroo courts” [326] and alleging that campuses disregard the due process rights of students accused of sexual assault. [327] Many of these critics argue that campus sexual assault cases should be handled by the criminal justice system. Some of these arguments, however, fail to recognize that Title IX provides civil rights protections to students in campus settings, similar to workplace settings that involve their own set of investigation and resolution processes. [328]

Documentaries on campus sexual assault, including The Hunting Ground and It Happened Here, have been another source of public awareness. Although these efforts have heightened understanding of campus sexual assault, some have unfairly portrayed all campuses as unwilling to address sexual assault by silencing victims and ignoring reports of assault.

SARTs can optimize collaboration and relationship-building with campus partners by noting the effect on campuses of both the media landscape and any existing or pending federal and state legislation.

For additional information on collaboration with the media, see the section on Working with the Media in the SART Toolkit.

Campuses are required to comply with federal legislation and guidance in addressing campus sexual assault. Below is a list of the existing legislation and federal guidance that campuses typically reference. Familiarity with these items is essential for campuses and for SARTs that partner with campuses.

Title IX states: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” [329]

The Department of Education — through its Dear Colleague Letters, listed below — has interpreted Title IX to include preventing and addressing sexual assault and harassment and any retaliation as a result of reporting such victimization. Title IX requires that when a school knows or reasonably should know of possible sexual assault, it must take immediate and appropriate steps to investigate, address the effects of the harm, and prevent its recurrence.

This legislation requires campuses to collect information on certain crimes and report them annually to the public. The report must also contain information about support for victims of violence, as well as the institution’s policies prohibiting violence. The Annual Security Report must be distributed to all staff, faculty, students, prospective students, and employees.

VAWA Amendments to Clery (2014) [330]

The amendments to the Clery Act, outlined in the 2014 Reauthorization of the VAWA, are frequently referred to as the Campus Sexual Violence Elimination Act (Campus SaVE), or Section 304 of the VAWA Amendments to Clery.

Incorporated into the Reauthorization of VAWA, the SaVE Act requires campuses to expand their policies, data collection, prevention programs, and response services to include dating and domestic violence and stalking. The act also requires campuses to provide all incoming students, faculty, and staff with information about preventing and responding to campus interpersonal violence and to demonstrate that the school provides ongoing, evidence-based prevention programs on these topics.

The act requires that campuses provide specialized training for those professionals who work on interpersonal violence on campus. Finally, it requires that campuses outline possible sanctions for violations of their institution’s policy and interim measures that student victims can access to reduce barriers.

Sexual Assault Survivors’ Rights Act (2016) [331]

Under this legislation, victims may not be charged for undergoing a medical forensic examination, regardless of their decision about reporting to law enforcement. In addition, the evidence collected during the exam must be preserved until the statute of limitations runs out, and victims will be able to request that authorities contact them before the end of the statute of limitations and the destruction of the evidence. Finally, under this law, victims have the right to be notified if a DNA match identifies the offender, and if the results from the kit or any toxicology testing are found to be positive.

Although this law is not specific to campuses, many campuses may see an increase in victims who have access to their medical forensic exam results and who wish to include these results as evidence in campus adjudication proceedings.

Dear Colleague Letter (2010) [332]

This guidance instructs institutions receiving federal financial aid funds that, to be compliant with Title IX, they must prevent sexual harassment and gender-based harassment. The Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights Schools is authorized to fine schools that do not comply.

Dear Colleague Letter (2011) [333]

This is the guidance most schools point to as changing the history of campus sexual assault prevention and response efforts. This letter instructs institutions that they must publish and disseminate a policy prohibiting sexual assault and designate someone to coordinate reports of sexual assault, typically a Title IX coordinator.

Most importantly, this letter indicates to campuses that their investigations must use the preponderance of the evidence standard in finding violations. Criminal standards, such as clear and convincing, are not acceptable for campuses to use in determining policy violations. The letter also directs that campuses have a 60-day timeframe for conducting prompt and equitable investigations.

Questions and Answers on Title IX and Sexual Violence (2014) [334]

This document provides guidance on the following topics:

The letter also answers questions about training requirements for campus personnel who conduct investigations, and protections from retaliation against students who report.

White House Not Alone Report (2014) [335]

This report from the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault advises campuses to provide all personnel responsible for responding to sexual assault with specific training on providing a trauma-informed response. The report also includes a task list for campuses when revising their sexual misconduct policies to align with the amendments to the Clery Act.

Campus climate surveys on sexual assault are recommended to better understand, prevent, and respond to incidents of sexual assault. Prevention approaches informed by the work of the CDC are recommended, and campuses are urged to increase bystander intervention training and programs to engage men.

The report also suggests that campuses provide confidential victim advocates for victims of sexual assault. Finally, the report encourages campuses to partner with local agencies to strengthen their prevention and response efforts.

Between 2013 and 2015, 23 states proposed legislation on campus sexual assault. Of those, 10 states passed legislation in 4 general areas: consent, law enforcement’s role in campus sexual assault, transcript notations for students found in violation of school policy, and the role of legal counsel in a campus process. Additionally, between January and October 2016, an additional seven states passed legislation in those four areas. Understanding existing and proposed state legislation on sexual assault that impacts campuses is important for community partners and SARTs seeking to work on campuses. [336]

For current information on campus sexual assault legislation, refer to Campus Technical Assistance Providers in the SART Toolkit.

Campus climate surveys are designed to gather data on the prevalence of sexual assault on a given campus. Campus climate surveys vary greatly, yet most are designed to gather more detailed information on campus sexual assault incidence rates than are available through other nationally representative surveys. Some campus climate surveys also assess for specific topics, such as perpetration behavior and awareness of campus resources. Although not federally legislated, these surveys provide important information as campuses work to develop and strengthen their sexual assault prevention and response efforts.

The White House Not Alone Report recommended that campuses conduct climate surveys annually, though experts have recently disagreed with that frequency and have suggested that every other year is a preferred timeframe. The White House report urged campuses to conduct these surveys voluntarily, but also stated that the White House would work to require compliance via legislation. Indeed, the Campus Accountability and Safety Act (CASA), introduced in 2014, contains a provision requiring campuses to conduct biennial campus climate surveys.

To comply with the White House Report recommendations, many campuses developed their own campus climate surveys. Other organizations, including the AAU and the Higher Education Data Sharing Consortium, developed campus climate surveys, some of which campuses could purchase and customize. A group of faculty researchers, the Administrator Researcher Campus Climate Collaborative (known as ARC3), developed a template survey that campuses may use for free.

The White House commissioned a pilot survey with Rutgers University, which the OVW later expanded to include nine other campuses. The results were shared widely, and the Campus Climate Survey Validation Study Final Technical Report is available. [337]

Campuses and SARTs working with campuses can review surveys to determine which might best meet their specific needs. For a useful side-by-side comparison of the climate surveys available for use by campuses, see Climate Surveys: An Inventory of Understanding Sexual Assault and Other Crimes of Interpersonal Violence at Institutions of Higher Education. [338]

Campus climate surveys are often developed and implemented by a committee, which presents an important opportunity for SARTs to partner with campuses. The college or university may charge an existing committee with conducting a campus climate survey, such as a SART committee, or a CCR team. The climate survey team may involve offices not usually engaged with either SART or CCR teams, such as the Office of Institutional Research.

SARTs can serve as invaluable content experts, ensuring that survey items are trauma-informed, and that appropriate campus and community resources are embedded throughout the survey instrument. In addition, SARTs may be aware of information that is unknown or unfamiliar to campus administrators (e.g., incidence trends that can enhance survey dissemination or barriers to survey completion).

Collaboration with community partners may help campuses prepare for an increase in reporting or in the number of students seeking services as a result of the survey and any survey marketing efforts. Finally, SARTs can also assist in disseminating the survey in off-campus locations that students might frequent.

Once a survey is complete, community partners or SARTs can help analyze and interpret the results and develop an action plan to address any gaps identified by the data. For example, a SART could help the campus provide additional training for staff or additional prevention and awareness outreach programs both on and off campus.

Campus Climate Survey Validation Survey Fact Sheet (PDF, 2 pages)

This resource from the Office on Violence Against Women (OVW) provides tips and methods for conducting a climate survey.

Student Action Packet on Campus Climate Surveys (PDF, 21 pages)

This resource from OVW helps students understand how to conduct a climate survey on their campus.

SARTs can optimize their work with a student population by familiarizing themselves with the institution’s policies on sexual assault, domestic violence, and stalking on campus, as well as reporting options for victims. These policies are often long documents written in legal language that may be hard for students to understand. SARTs can help interpret these policies to provide clear information for students.

SARTs also can help ensure that campus representatives list community contact information and services in the campus policy so that students are aware of their off-campus service options.

It is vital that victims of campus sexual assault understand their reporting options, and that reporting options differ from disclosure options; victims need to understand who they can talk to about an assault without compromising their confidentiality. Many campuses list “reporting options” on their websites and include these along with disclosure options. By helping campus administrators distinguish between reports and disclosures — and helping students understand the difference — SARTs and community partners can help to ensure students have access to confidential, privileged support on campus and within the community.

When a student makes a report to a campus official or responsible employee, the campus is considered “on notice” and, under Title IX, must take steps to investigate the incident. The Title IX Office or Student Conduct office may undertake the investigation, which will optimally be led by a trained individual. The institution has a 60-day timeframe for investigating and resolving such cases. The victim has a right to interim measures or support services during the investigation and beyond, regardless of the outcome of the case. The process of investigation and adjudication varies from campus to campus. Campuses must also offer students safe places or persons to whom a student can disclose a sexual assault, without initiating a formal investigation.

On many campuses, victims can choose to report through sworn law enforcement officers on campus. The report is then forwarded to local law enforcement agencies, or through the law enforcement agency that has jurisdiction over the campus. If the campus does not have sworn law enforcement officers, students have the option to report directly to the law enforcement agency with jurisdiction for their campus.

Students may choose to work with a campus or community victim advocate during that process. Campuses should provide accommodations for students who are engaged with the law enforcement reporting process, such as working with professors to make up work missed during court appointments.

Student victims may choose to report both to the campus and local law enforcement. The campus report may result in immediate interim measures that the victim may find helpful. However, to minimize the trauma experienced by the victim, one must consider the burdens placed on the victim throughout the two processes.

SARTs and campus case management teams can coordinate their responses to help victims navigate both these systems and to facilitate regular communication on the two investigations. SARTs can be instrumental in developing processes and policies to support victims as they navigate reporting a sexual assault.

SARTs are often well-positioned to work with campuses in developing support services for victims. The needs of specific victims — with particular emphasis on culturally appropriate services — will drive the design of victim services. Most importantly, the services must be accessible to and appropriate for the many populations that comprise the campus community (e.g., students, faculty and staff, men, individuals with disabilities, cultural and religious minorities, LGBTQ individuals, commuting students, international students, students who are parents, older students). In addition, response services should be available through both campus- and community-based organizations.

Serving Victims of Campus Crime, a National Criminal Justice Association project, has identified the critical elements of a comprehensive victim services program on a college or university campus, including the following:

SARTs can also help design interim measures and academic accommodations for victims on campus. Victims should have access to a range of supportive options, regardless of whether they choose to officially report to campus officials and irrespective of whether their assailant is a student.

The White House Task Force issued a sample list of supportive measures, interim measures, and academic accommodations that campuses should consider when working with victims, including —

Academic accommodations can include —

The interim measures that should be implemented and how they should be implemented vary from one case to another. For a list of examples, see Questions and Answers on Title IX and Sexual Violence. [339] Additionally, when implementing interim measures, schools should seek to minimize the burden on the victim.

Many opportunities exist for meaningful collaboration between campuses and SARTs or other community agencies. When developing relationships and working together, campuses and SARTs may sign MOUs to define and describe those relationships. MOUs may be required for campuses as part of grant applications or to receive funding. Any SART, agency, or agencies entering into an MOU should evaluate the MOU to ensure it is meaningful and appropriate for the collaboration. SARTs can also be proactive in reaching out to campuses to make connections. SARTs’ partnerships with campuses can lead to significant improvements in campus prevention and response efforts.

By including campus representatives in community SART meetings, SARTs create an opportunity for regular communication between the campus and community partners. If the campus has a victim advocate, attendance allows the advocate to receive updates on the status of law enforcement cases and enables the advocate to share timely information with the students with whom they are working. This may also afford the opportunity for a campus-based advocate to share information about co-occurring Title IX cases. This communication facilitates better coordination on behalf of victims who may be engaged in different reporting processes while also managing their academic work.

For campuses without victim advocates, collaboration with a SART allows the campus representative to better understand the community responses to sexual assault, including services, medical forensic exams, law enforcement investigations, and prosecutions.

In response to the increasing number of cases being reported to campus officials, many institutions have created sexual assault case management teams to address Title IX-related cases involving a campus investigation or a campus law enforcement investigation. The team often consists of a Title IX coordinator or investigator, student conduct staff, campus or community victim advocates, and campus law enforcement. These teams are not meant to take the place of a community SART and can benefit from collaboration with a SART.

SARTs can inquire whether campuses within their service area convene case management meetings and, if so, ask to participate. Because some student victims seek advocacy services off campus even when campus advocates are available, coordination between any existing agencies or teams addressing sexual assault is important. Campuses can benefit from the expertise of SARTs, and SARTs can learn about campus efforts and how to best assist victims who are students.

The inclusion of community partners on CCR teams and case management teams, and the inclusion of campus representatives on community SARTs, helps to ensure that partnerships are meaningful and contribute to a trauma-informed, victim-centered response to sexual assault. All partners may wish to clarify the role of each through an MOU. By working together, campus-based teams and committees, and SARTs and other community agencies, can have the broadest impact in improving responses to campus sexual assault.

“We really focused on including the different reporting options and differentiating between confidential, privileged, and mandatory reporting on and off campuses. Having the Title IX Coordinators attend SART meetings has helped with these conversations. Most of them drafted their policies/procedures on campus.”

— Nikki Godfrey, MSW Campus/Stalking/PREA Project Coordinator WV Foundation for Rape Information and Services (WV FRIS) www.fris.org

Students are most likely to seek resources online through website searches on a computer or a mobile device. By reviewing their own and each other’s websites, SARTs and campuses can determine what campus and community information is available and identify and fill any knowledge gaps.

In addition to online outreach methods, passive awareness campaigns can also be effective. For instance, the University of California San Diego has placed crisis hotline information stickers in every residence hall bathroom. These stickers serve as a ready reminder to students about available and accessible resources. Other campuses post information on the back of all public bathroom stalls, and some purchase Facebook advertising to promote their website and departmental resources targeting their student populations.

An effective way to determine students’ awareness of campus and community support services is by conducting a community needs assessment or campus climate survey. These survey tools often ask specific questions to assess awareness of resources available to victims of sexual assault. Together, campuses and communities can analyze the data and develop a strategic plan to reduce any gaps and target awareness campaigns toward specific populations (e.g., Greek letter organization students, athletes, student leaders, international students, students from underrepresented populations).

Listed below are ideas to help SARTs and schools that are working to increase student awareness of sexual assault services and sexual assault forensic medical exam services:

Given that most campus sexual assaults occur between acquaintances, campus administrators and students may feel that pursuing a medical forensic exam is unnecessary. Both victims and administrators need targeted education and outreach about the benefits — and limitations — of participation in this type of exam.

The majority of student victims experience drug- and alcohol-facilitated sexual assault. In states where law enforcement reports are required to include a medical forensic exam, students may be reluctant to or dissuaded from pursuing this option. In these cases, campuses and community SART agencies can partner to educate students about both community and campus amnesty policies for victims.

Student victims often hesitate to request hospital treatment and medical forensic exams for fear their parents will be notified. In cases where follow-up STI tests or medication are not provided by the hospital, students should be informed of any on-campus health services the campus provides. Again, a partnership between campuses and SART agencies can help students understand how to protect the confidentiality of their cases while accessing any available campus resources.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) is a federal law that protects the privacy of student education records. [340] The law applies to all schools that receive funds under an applicable program of the U.S. Department of Education. In the past, some campus administrators had used FERPA as an excuse not to disclose the outcomes of sexual assault complaints to victims. They interpreted the law to mean that disclosing outcomes was a violation of the rights of an accused student.

The 2001 Dear Colleague Letter (DCL), issued by the Department of Education, explicitly outlines the intersections between FERPA and Title IX: “If there is a direct conflict between the requirements of FERPA and the requirements of Title IX, such that enforcement of FERPA would interfere with the primary purpose of Title IX to eliminate sex-based discrimination in schools, the requirements of Title IX override any conflicting FERPA provisions.” [341]

The 2011 DCL goes further and indicates that the notification of outcomes should occur, regardless of a finding of a code of conduct violation. “When the conduct involves a crime of violence or a non-forcible sex offense, FERPA permits a postsecondary institution to disclose to the alleged victim the final results of a disciplinary proceeding against the alleged perpetrator, regardless of whether the institution concluded that a violation was committed.” [342]

By understanding the requirements of FERPA, SARTs that work with campuses or participate in campus response teams are prepared to refrain from sharing information that violates the law. These SARTs will be poised to advocate for the confidentiality of victims protected by FERPA.

Under FERPA, those accused of committing a sexual assault have a right to inspect and review portions of the complaint that directly relate to them. In such cases, the school must redact the victim’s name and other identifying information before allowing the alleged offender to review the relevant sections. Where the school is required to report the incident to local law enforcement or other officials, however, the school may not be able to maintain the complainant’s confidentiality. [343]

A Hidden Crisis: Including the LGBT Community When Addressing Sexual Violence on College Campuses (PDF, 8 pages)

This issue brief, written by Zenen Jaimes Pérez and Hannah Hussey, was posted by the Center for American Progress in 2014.

CALCASA/PreventConnect Campus Resources

CALCASA’s PreventConnect site houses resources on campus sexual violence prevention, such as podcasts, videos, webinars, and newsletters.

Improving Campus Sexual Assault Prevention

This guide by EVERFI provides an overview of the current state of sexual assault on campus, its effect on victims and their schools, how institutions of higher education are currently responding, and clear, evidence-based guidelines for a comprehensive prevention approach.

This advocacy group, founded in 2013, aims to inform students of their right to an education free from gender-based violence under Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in institutions receiving federal government funding.

This listserv promotes ongoing dialogue and information sharing among community and professional organizations and agencies that respond to sexual assault. It supports the safety, justice, and autonomy of all victims; works to meet the needs of underserved and marginalized victims; and creates a forum to enhance the response to systems advocacy and sexual assault prevention initiatives among SARTs.

This email group is a forum for discussing the latest efforts for preventing violence against women. Topics include developing prevention strategies, identifying and assessing prevention materials, discussing policy initiatives, developing partnerships for prevention, and developing community organizing strategies.

Preventing and Addressing Campus Sexual Misconduct: A Guide for University and College Presidents, Chancellors, and Senior Administrators (PDF, 14 pages)

The White House Task Force, 2017, developed this guide to support university administrators in responding to sexual assault on campus.

Transgender Sexual Violence Project

FORGE provides a wide range of assistance to anti-violence professionals who seek to provide competent and respectful care to transgender victims of sexual assault, domestic and dating violence, stalking, and hate violence.

The Blueprint for Campus Police: Responding to Sexual Assault (PDF 174 pages)

This resource by the University of Texas at Austin Institute on Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault School of Social Work provides a multi-level approach to the complex problem of campus sexual assault that builds upon the existing body of knowledge and recognizes the need for identifying emerging best practices.

Campus Sexual Assault, A Systematic Review of Prevalence Research from 2000-2015

This study by Lisa Fedina, Jennifer Lynne Holmes, and Bethany Backes is the first to systematically review and synthesize prevalence findings from studies on campus sexual assault.

The Handbook for Campus Safety and Security Reporting (PDF, 265 pages)

This handbook by the U.S. Department of Education offers procedures, examples, and references for higher education institutions to follow in meeting the requirements of the Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act.

In response to the increased national attention to campus sexual assault in recent years, a growing number of organizations offer content expertise. It is important to know the background of the staff of these organizations as it greatly affects their approach to programs and services. For example, those with a law background see the issues from a liability perspective while organizations staffed by those with a law enforcement background bring that perspective to Clery Act compliance.

Some campuses feel that paying top dollar for prevention programs or training for staff and faculty reflects their commitment to the issue. The most important consideration when choosing a technical assistance provider is making sure the provider will help the campus implement the most effective prevention and response programs possible.

Below is a list of organizations frequently used by campuses, as well as a list of nonprofit organizations that provide low-cost training and content expertise.

Association of Title IX Administrators

ATIXA provides investigator training for campus Title IX coordinators.

This organization facilitates online prevention education programs for students, faculty, and staff.

National Center for Campus Public Safety

This center offers trauma-informed sexual assault investigation and adjudication training.

National Center for Higher Education Risk Management (NCHERM)

NCHERM provides legal representation for colleges and universities.

National Center for Victims of Crime

The NCVC is a nonprofit organization that advocates for victims’ rights, trains professionals who work with victims, and serves as a trusted source of information on victims’ issues. The NCVC serves as a comprehensive national resource committed to advancing victims’ rights and helping victims of crime rebuild their lives. At its core, the NCVC is an advocacy organization committed to — and working on behalf of — crime victims and their families.

National Crime Victim Law Institute

NCVLI is a nonprofit legal education and advocacy organization whose mission is to actively promote balance and fairness in the justice system through victim-centered legal advocacy, education, and resource sharing.

The Rape Abuse Incest National Network (RAINN) provides information, resources, and technical assistance for organizations on campus sexual assault.

Below is a list of nonprofit organizations with content expertise on campus sexual assault. The first list contains organizations with which the DOJ, OVW contracts to serve as technical assistance providers to recipients of the Campus Grants Program. The area of technical assistance is also listed. Due to their extensive content expertise, these organizations can serve as rich resources for grantees and non-grantees alike.

Black Women’s Blueprint Project

Black Women’s Blueprint focuses on inclusive prevention programs and response services.

California Coalition Against Sexual Assault

CALCASA provides assistance in the areas of campus prevention, public policy, and advocacy.

Clery Center for Security on Campus

Clery Center trainings include videos, books, courses, and workshops.

East Central University Trainer Development Program

This free program helps build skills for campus law enforcement related to sexual and gender-based violence.

Green Dot provides training in bystander intervention programs.

Topics covered by Men Can Stop Rape include men’s engagement and healthy masculinity.

Mississippi Coalition Against Sexual Assault

This Mississippi Coalition Against Sexual Assault offers trainings on topics including first responder and crisis management, campus SARTs, and prevention.

Oregon Sexual Assault Task Force

The Oregon Sexual Assault Task Force focuses on community and campus partnerships on sexual violence and provides trainings on prevention, a SANE program, and a multidisciplinary Sexual Assault Training Institute.

Prevention Innovations Research Center

This center focuses on research in the areas of bystander intervention programs, campus climate surveys, and campus sexual and relationship violence prevention.

The Victim Rights Law Center has expertise in civil legal representation of survivors. The center also trains victim advocates, attorneys, school administrators, medical personnel, law enforcement officers, and others in areas such as Title IX compliance and survivor response services.

Sexual violence in correctional facilities (jails, prisons, community corrections, lockups, and juvenile facilities) has long gone largely unaddressed by most systems in our country. Recently, thanks to funding from the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), more is known about the frequency and nature of sexual violence in correctional facilities, and how important it is that incarcerated survivors have access to services.

Since the passage of the Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003, statistics have been gathered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) around the prevalence of sexual violence, demonstrating — [344]

We also know that certain populations are targeted for sexual violence in correctional institutions: [345]

The Prison Rape Elimination Act of 2003 requires the BJS to carry out a comprehensive statistical review and analysis of the incidence and effects of prison rape for each calendar year. BJS’s review must include, but is not limited to, the identification of the common characteristics of both victims and perpetrators of prison rape, and prisons and prison systems with a high incidence of prison rape.

This section of the SART Toolkit covers the following topics:

The Prison Rape Elimination Act was passed in 2003 with unanimous support from both parties in Congress. [346] The purpose of the act is to “provide for the analysis of the incidence and effects of prison rape in federal, state, and local institutions and to provide information, resources, recommendations, and funding to protect individuals from prison rape.” [347] In addition to creating a mandate for significant research from the BJS and through the NIJ, funding through the BJS and the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) supported major efforts in many state correctional, juvenile detention, community corrections, lockups, and jail systems.

The act also created the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission and charged it with developing draft standards for the elimination of prison rape. The Prison Rape Elimination Act Standards were published in June 2009, and were turned over to DOJ for review and passage as a final rule. [348] That final rule became effective August 20, 2012.

There are four separate sets of standards:

In 2010, the Bureau of Justice Assistance funded the National PREA Resource Center to continue to provide federally funded training and technical assistance to states and localities, as well as to serve as a single-stop resource for leading research and tools for all those in the field working to come into compliance with the federal standards.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) was established to apply to any type of detention facility in the United States, U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia. The DOJ oversees PREA compliance for prisons, jails, lockups, community confinement centers, and juvenile detention centers operating in the United States and U.S. territories. PREA also applies to DHS confinement facilities.

PREA standards require that facilities falling under the adult prisons and jails, juvenile facilities, or community confinement standards be audited once every three years by a DOJ-certified PREA auditor.

PREA compliance is determined by a DOJ-certified PREA auditor who will assess the facility based on all items in the applicable set of PREA standards. To be compliant, the facility must meet all items of each standard.

While the PREA standards apply to all detention facilities in the U.S. and U.S. territories that are within the DOJ, the DOJ can only levy financial penalties for non-compliance on state or territorial governments. Each year, the state or territory’s governor is required to submit a letter of assurance to the DOJ, stating that the state-run corrections facilities are either in compliance with the PREA standards or are working toward compliance. Some states have also chosen to submit a letter stating their opposition to the standards or not submit a letter at all.

If the state submits an assurance that they are working on compliance with the standards, 5 percent of certain grant funds must be held aside to help the state get into compliance. If the state does not submit a letter or writes that they do not intend to comply with the standards, the state loses 5 percent of funds from designated grant streams.

Please note that these are definitions from the national PREA standards and may vary from state law.

Sexual abuse of an inmate, detainee, or resident by another inmate, detainee, or resident includes any of the following acts, if the victim does not consent, is coerced into such act by overt or implied threats of violence, or is unable to consent or refuse:

Sexual abuse of an inmate, detainee, or resident by a staff member, contractor, or volunteer includes any of the following acts, with or without consent of the inmate, detainee, or resident:

Repeated and unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or verbal comments, gestures, or actions of a derogatory or offensive sexual nature by one inmate, detainee, or resident directed toward another.

Repeated verbal comments or gestures of a sexual nature to an inmate, detainee, or resident by a staff member, contractor, or volunteer, including demeaning references to gender, sexually suggestive or derogatory comments about body or clothing, or obscene language or gestures.

It is important for SARTs to be aware of the correctional facilities in their area and be aware of and understand what protocols are in place to address sexual violence. Community-based SARTs and correctional facilities or correctional-based SARTs may seek to review and develop joint protocols as needed. Establishing a working relationship and MOUs with correctional facilities before an assault occurs can help all members of a SART know how to best respond.

SARTs help ensure responses are consistent and timely to all incidents of sexual violence. Although policies and procedures for sexual assault response are defined in the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) standards, each institution has some flexibility to implement these policies in their own way.

Typically, institution-based SARTs include a PREA compliance manager, a correctional officer (investigator), and medical service personnel. [349] These individuals receive training, including SART-specific training, and may collaborate with community-based agencies or SARTs.

Institution-based SARTs assist with streamlining processes of prevention and response within an institution. They can help to ensure the collection of high-quality evidence, contribute to more successful prosecutions, and help make sure that victims of sexual abuse get the help they need.

Developing Facility-Level SARTs (multimedia, 1:28:09)

This webinar, presented jointly by Just Detention International (JDI) and the National PREA Resource Center, provides corrections officials with practical guidance on how to create a coordinated response to sexual abuse victims within their institutions. This webinar covers the basics of how to build a facility-level SART, including how to get started, who should be involved, and how to develop a SART protocol.

How to Implement an Institution-Based Sexual Assault Response Team (SART) (PDF, 8 pages)

This guide by Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape (PCAR) was created as a quick resource to provide information on how to develop an institutional SART which will work in conjunction with the local community-based SART.

National PREA Resource Center Curricula

The curricula offered by the National PREA Resource Center cover the topics of investigating and preventing sexual abuse in detention facilities.

PREA & The SART Response (PDF, 10 pages)

This resource from the Wisconsin Adult Sexual Assault Response Team Protocol breaks down the responsibilities of various agencies represented on a SART in cases of inmate-on-inmate and staff-on-inmate sexual assault.

These tools, provided by JDI, include an evaluation form, a SART protocol, several MOUs, an informed consent form, and a counseling intake form.

Within correctional facilities, law enforcement officers will participate in receiving a report and ensuring the safety of the survivor and the integrity of the investigation. [350] Protocols will outline who is responsible for which actions, but law enforcement generally will be part of completing an investigation, interviewing witnesses, collecting evidence, and holding perpetrators accountable. Law enforcement may be involved in transferring a victim within the facility or to the appropriate location for a medical forensic examination.

The Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) standards require corrections facilities to accept reports from incarcerated people verbally, in writing, anonymously, and where the perpetrator is not named. The standards further require the facility to accept reports from third parties and via a designated, external reporting mechanism.

Every allegation or report of sexual abuse or sexual harassment within a corrections institution must be investigated according to the correction facilities policies and protocol. The standards set forth requirements for gathering and preserving evidence, conducting compelled interviews, determining witness credibility, conducting administrative and criminal investigations, making referrals for criminal prosecution, and retaining records. It is important to note that investigations inside detention facilities can be administrative or criminal investigations and can be conducted by internal or external investigators.

The facility almost always starts the administrative investigation — meaning an investigation into conduct that violates facility policy or rules to determine if there should be disciplinary action. Correctional facilities that conduct their own administrative investigations into sexual abuse or harassment reports must do so promptly, thoroughly, and objectively as mandated by PREA. If it appears that a crime, according to the jurisdiction’s laws, was committed, there must also be a criminal investigation to determine if there was a crime and to present such evidence to a prosecuting authority.

Some facilities have the capacity and legal authority to conduct criminal investigations within their own facilities. Often such investigations are conducted by an internal affairs department. Regardless of who completes them, all investigations must be prompt, thorough, and objective. In addition, agencies must use investigators who have received special training in conducting sexual abuse investigations within a detention setting.

The PREA standards state that an investigation must not be terminated because the alleged perpetrator has left the facility or agency — by resigning or being fired if they are a staff member, or by being released or transferred if they are an inmate.

Important Information About Administrative Investigations

It is critical to remember that an administrative investigation uses “a preponderance of the evidence” as the evidentiary standard for determining whether there was a violation. A preponderance of the evidence is “just enough evidence to make it more likely than not that the fact the claimant seeks to prove is true.” [351]

As the evidentiary standards between administrative and criminal investigations are different, there may be different outcomes in each investigation. The PREA Resource Center has a curriculum entitled Human Resources and Administrative Investigations for those that are conducting administrative investigations involving staff, contractors, or volunteers. [352]

In most states, corrections officers are not sworn law enforcement; therefore, they will only be responsible for conducting an administrative investigation in PREA-related cases. As cases involving staff, contractors, or volunteers may be particularly complex, it is extremely important that the administrative investigators coordinate with the criminal investigators in terms of the process and flow of both investigations. It is very important that the administrative investigation not compromise the criminal investigation and any future criminal charges and prosecution of those charges.

For those that are conducting administrative investigations involving inmate-on-inmate sexual assault, the same requirement for specialized training listed above is required. That training, Investigating Sexual Abuse in Confinement Settings, applies to both criminal and administrative investigators. [353]

Criminal Investigations

It is critical to remember that a criminal investigation uses “beyond a reasonable doubt” as the evidentiary standard for determining whether to press charges.

The International Association of Chiefs of Police has developed a video entitled Investigating Sexual assault and Sex Related Crimes in Confinement Settings — Guidance for Criminal Investigators, accompanied by a Resource Guide. This resource for criminal investigators was produced in 2015.

Investigating Sexual Abuse in Confinement Settings [354] is designed for any individual conducting a criminal or administrative sexual abuse investigation in confinement settings, addressing PREA Standard §115.34/.134/.234/.334. This training is designed to be led by an instructor and has nine modules. This curriculum was created by The Moss Group.

PREA Investigating Sexual Abuse in a Confinement Setting Course [355] is also designed for individuals who will be conducting either criminal or administrative sexual abuse investigations in a confinement setting. This training is provided in an online format for those that do not have the resources or have personnel in need of the training to provide the more extensive training above. This curriculum was developed and is maintained by the National Institute of Corrections.

Prosecution is a critical piece in ending prison sexual abuse. Although prosecutors are not regulated under the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) standards, their responsibility to seek justice extends to victims who are incarcerated.

Several issues relevant for prosecutors are challenging within corrections facilities. For example, evidence preservation, sustaining victims’ involvement, and preventing witness intimidation all look different in detention than they do in the community. For more information, see resources for prosecuting cases with incarcerated survivors.

It is important that community-based SARTs work with local area detention center(s) to learn the facility’s policies and procedures, not only regarding sexual abuse, but also related policies and procedures such as how to handle grievances, discipline of staff and inmates, and protections for people who might be vulnerable to abuse. These conversations may serve to enhance connections around supporting survivors as well as investigations.

Deepening coordination between the administrative and criminal investigations is critical so that the investigators do not compromise each other’s work. The facility has specific timeframes they must meet, and it is essential to discuss them so that the administrative investigation does not hamper criminal investigators.

While each facility will have their own guidelines, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Department of Correction, Sexual Harassment/Abuse Response and Prevention Policy (SHARPP) may provide facilities or SARTs with an overview of topics to discuss or areas to clarify for prevention and response.

It is important that advocates be familiar with the incarceration setting. Many facilities are happy to provide tours of the facility to advocates, and even require it, prior to the advocate and any incarcerated victim receiving services. This allows the advocate to have a visual understanding of the surroundings the incarcerated victim deals with on a day-to-day basis. In fact, many facilities require advocates that will be working with incarcerated victims to complete safety training and orientation.

JDI has developed a guide, Hope Behind Bars: An Advocate’s Guide to Helping Survivors of Sexual Abuse in Detention. [356] This guide provides information and suggestions for working with incarcerated survivors through multiple service delivery methods such as hotline use, mail, and in-person services.

Just as survivors in the community have a right to an advocate being present in the examination room, so do incarcerated survivors. A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Forensic Medical Examinations – Adults/Adolescents 2nd Edition (2013) was updated to include information for SART members and corrections officials related to working with incarcerated survivors. Advocates should provide the same level of support and advocacy to an incarcerated victim as a victim from the community.

The difference will be the presence of correctional officers in the examination room. The charge of the correctional facility is the care, custody, and control of the inmate, and this is especially focused on when the inmate leaves the facility for other services, which provides for an escalated escape risk. Advocates will need to inform the victim of the limits to confidentiality in this situation. Advocates should also be conscientious of giving anything to the victim at that time.

Advocates should ask the corrections officer in the room if providing written materials is allowable. If not, the advocate will need to arrange to provide this information at the facility through the PREA Coordinator or PREA Compliance Manager.

Legal Accompaniment

Just as in the community, survivors of prison sexual abuse have the same rights to have an advocate provide accompaniment and advocacy when going through interviews for both administrative and criminal investigations, prosecutorial interviews, and court appearances.

In-Person Counseling

Providing services to incarcerated survivors requires work ahead of time on the part of both advocates and corrections officials. It will be important to work out the logistics of providing all services (i.e., phone, mail, in person). When providing in-person counseling to an incarcerated victim, it is important to discuss where this service will occur, what type of confidentiality is available, and what safety measures are in place.

Many facilities will allow advocates to provide these services in the attorney-client rooms. These rooms are monitored by camera but not by audio surveillance, and therefore confidentiality can be kept intact for the most part. By being on video surveillance by the staff, it also provides the advocate with a level of safety when meeting with the incarcerated victim.

Other places that may be considered are rooms in the medical department or the library when not in use. Being conscious of safety, it is important for both corrections staff and advocates to visit all potential counseling sites prior to the first call so that all parties are aware of how this service will occur and where.

The sexual assault forensic examiner (SAFE) or sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) plays an important and integral role in care of the incarcerated victim of sexual abuse. The medical examination itself will occur according to all the same standards as with any other victim of sexual abuse and in accordance with A National Protocol for Sexual Assault Forensic Medical Examinations — Adults/Adolescents 2nd Edition (2013).

It will be important to recognize that in addition to the community-based SART comprised of local law enforcement, prosecution, and victim services, corrections officials will also be present. It is extremely important for SAFEs to know of the PREA standards that apply to their role and the role of other team members in this situation.

PREA standards require that a victim advocate be made available to the victim to provide the regular advocacy and accompaniment services. To meet the PREA standards, victim advocates should be called immediately to provide the required services. In the same way as the victim advocates need to be aware of the presence of the corrections officers in the room, the SAFE nurses should be aware of the situation as the officers will remain present during the entire examination.

In some situations, the victim may remain handcuffed through the examination, and the examiner will need to communicate the need for uncuffing or other adjustments to complete the entire examination.

Once the examination is completed, the examiner will provide all follow-up documentation to the corrections officer to provide to the medical personnel at the facility. The forensic evidence collected in the “rape kit” will be handed to the criminal investigator in the case, just as in an assault occurring outside a correctional institution. Additionally, it will be important to understand that the medical department from the correctional facility may be in touch for follow-up questions, but will be able to provide an informed consent from the individual.

Building Partnerships Between Rape Crisis Centers and Correctional Facilities to Implement the PREA Victim Services Standards (PDF, 41 pages)

This guide by the PREA Resource Center addresses considerations to make when building partnerships, including how to frame issues, and challenges and promising practices.

Hope Behind Bars: An Advocate’s Guide to Helping Survivors of Sexual Abuse in Detention (PDF, 44 pages)

This guide by JDI provides information and suggestions for working with incarcerated survivors through multiple service delivery methods such as hotline use, mail, and in-person services.

Manual for Providing Services to Survivors of Sexual Assault and Abuse in South Carolina Correctional Facilities (PDF, 25 pages)

This 2016 manual includes information on PREA, victim service standards, program examples, and recommendations for working with people in custody who identify as LGBTQ.

Partnering with Community Sexual Assault Response Teams: A Guide for Local Community Confinement and Juvenile Detention Facilities (PDF, 88 pages)

This guide by Vera Institute of Justice is designed to assist administrators of local community confinement and juvenile detention facilities in collaborating with a SART.

The guide is organized into three sections:

PREA Advocacy Manual: Tools for Advocates Working with Incarcerated Victims of Sexual Violence in Wisconsin (PDF, 32 pages)

This guide by the Wisconsin Coalition Against Sexual Assault is intended to support advocates’ work in detention settings with incarcerated individuals.

Intimidation of Victims of Sexual Abuse in Confinement (multimedia, 85:34)

This webinar by AEquitas identifies strategies for investigations and prosecutions that build trust in the criminal justice system and provide multiple, safe, and confidential points of entry for potential reporters. In addition, it discusses victim and witness safety, retaliatory violence, verbal and physical intimidation, and financial and emotional manipulation.

Prosecuting Sexual Abuse in Confinement: A Case Study (multimedia, 1:31:54)

This webinar by the National PREA Resource Center includes investigative and prosecutorial strategies by using an actual case prosecuted at the local level.

The Prosecutors’ Resource on Sexual Abuse in Confinement (PDF, 56 pages)

This resource guide by AEquitas assists prosecutors in their work on cases involving sexual abuse and sexual harassment in confinement.

Specialized Training: Investigating Sexual Abuse in Correctional Settings (PDF, 15 pages)

This training module by the National PREA Resource Center on prosecutorial collaboration discusses the ways collaboration with law enforcement plays a vital role in prosecuting perpetrators in an institutional setting. Guidance is provided to law enforcement in required training under PREA Standard §115.34/.134/.234/.334.

Strategies in Brief: Identifying, Investigating, and Prosecuting Witness Intimidation in Cases of Sexual Abuse in Confinement (PDF, 14 pages)

This article by AEquitas for prosecutors focuses on witness intimidation related to cases of sexual abuse in confinement. The article explores the myriad ways in which witness intimidation might occur and the ways with which prosecutors can work with confinement facilities to identify, investigate, and prosecute these cases.

The military is a unique community with its own social structure, hierarchy, and even its own laws. Community-based victim service providers who are not familiar with the military may find it baffling and impenetrable. Military service providers who are not familiar with civilian services may find them confusing and inapplicable. When a sexual assault involves both civilian and military service providers, both parties must work together to support the victim effectively. [357]

Sexual assault is an ongoing concern in the military that incurs significant costs, impairs mission readiness (the ability of the armed forces to carry out assignments), and disrupts unit cohesion (the bond between service members that sustains their will and commitment to each other, the unit, and their mission accomplishment). Sexual violence (assault, harassment, explicit images) impacts national security as it could place service members in compromising positions related to bribes or retaliation and, at a minimum, undermines good order and discipline. [358]

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) estimates that approximately 14,900 service members experienced sexual victimization during fiscal year (FY) 2016. However, the DoD received only 6,172 reports of sexual assault against service members during FY 2016. Data from the Workplace and Gender Relations Survey for Active Duty Members indicates that 0.6 percent of active duty men and 4.3 percent of active duty women suffered a sexual assault during FY 2016. [359]

Sexual assault and sexual harassment are also persistent problems at military service academies. During academic program year (APY) 2015-2016, 12.2 percent of women and 1.7 percent of men attending military service academies indicated that they experienced unwanted sexual contact. Almost half of women (48 percent) and 12 percent of men attending military service academies indicated that they experienced sexual harassment during APY 2015-2016. [360]

While the percentage of reported incidents has increased, the DoD estimates that about two-thirds of victims did not report in 2016. [361] The military is targeting the gap between prevalence and reporting to encourage reporting and has improved prosecution efforts of sexual assault and sexual harassment, as evidenced by a steady increase in the number of cases that are court-martialed. [362] The military has also demonstrated a hasty response to sexual harassment. [363]

Unfortunately, retaliation against victims who report remains an ongoing problem in the military. Out of active duty service members who reported a sexual assault during FY 2016, 58 percent admitted experiencing negative outcomes that they interpreted as retaliation, such as maltreatment, ostracism, or professional reprisal. Senior enlisted leaders, unit commanders, and other figures in victims’ chains of command were common culprits, according to women who indicated that they experienced reprisal and maltreatment. Nine out of 10 female service members who experienced sexual assault and perceived professional reprisal believed that leadership behavior harmed their careers. [364]

SARTs working with the military must be aware of the differences between civilian and military communities as well as the unique impact sexual assault has on victims in the military. Understanding the victim’s community may assist service providers in helping the victim heal, seek care, and receive justice.

Over the last decade, the DoD has made great strides to end sexual assault in the military by establishing the Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office (SAPRO) in 2005, clarifying and sometimes creating sexual assault and harassment policy, conducting training for all military staff, and continuing to execute existing programs and plans.

Charged with oversight of DoD sexual assault policies and programs, SAPRO focuses on preventing sexual assault, improving victim access to services, increasing the frequency and quality of information provided to victims, and expediting the handling and resolution of sexual assault cases. DoD sexual assault policies apply only to service members and dependent family members 18 years of age or older. Civilian employees not otherwise eligible for services receive care and treatment in the local community. Dependent family members under the age of 18 who are victims of sexual abuse receive services from the appropriate military Family Advocacy Program.

Among the requirements set forth in various DoD directives, the Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force must —

Visit the SAPRO for additional information. Consult DoD Directive 6495.01: Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Program, DoD directive 6495.02: Sexual Assault Prevention and Response (SAPR) Program Procedures, and DoD Instruction 6400.07 Standards for Victim Assistance Service in the Military Community. The Coast Guard has unique SAPR instructions outlined in the SAPR Commandant Instructions.

The military analyzes data each year to better prevent and respond to sexual assault, and to encourage reporting. Since the military is roughly 85 percent male, it is estimated that, in absolute numbers, more men experience sexual assault each year than women, although the DoD receives more reports from women than men. [366] Between 2012 and 2016, the military made specific strides to enhance reporting and supportive services to male-identified service members. These efforts led to more men reporting sexual assault in 2016 than ever before. [367]

Men who indicated experiencing a sexual assault on the 2016 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members most often indicated the following as reasons for not reporting: [368]

As opposed to women, more men categorize a sexual assault as hazing or bullying, and experience more multiple instances. [369]

In 2016, the DoD released the Plan to Prevent and Respond to Sexual Assault of Military Men to outline specific tasks and efforts related to prevention, service enhancement, reporting, and accountability for sexual assault against male service members.

In establishing relationships with those who treat veterans for military sexual assault, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is crucial. Most victims of sexual assault do not report to support services immediately following the assault. [370] Many veterans do not disclose sexual assault during their time of service, and seeking assistance may exacerbate existing trauma.

Veterans may be at increased risk of sexual assault after their military service, particularly those with mental or physical disabilities or those without appropriate housing.

The VA provides eligible veterans with confidential counseling and treatment for sexual trauma. In addition to counseling, related health care services are available at VA medical facilities. It is important that service providers and veterans know that counseling for sexual trauma is available regardless of whether the incident was ever reported.

To fully address the needs of and provide treatment for all victims of military sexual assault, collaboration between the military and civilian communities is vital. Communication is an essential cornerstone to any collaboration. First responders and other key personnel in both communities can establish relationships to ensure appropriate care for all victims of sexual assault. Developing a multidisciplinary approach, such as cross participation on SARTs, will ensure comprehensive and consistent responses to sexual assault from the military and civilian communities.

As an organization with its own laws, social customs, and practices, the military requires protocols, procedures, and accountability mechanisms that preserve and ensure readiness. The military justice system comprises three elements that work together: the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, and commanders.

The UCMJ is the federal law that defines the military justice system and lists criminal offenses under military law. The articles within the UCMJ define the offenses, which are frequently referred to by an article number. The UCMJ provides commanders with broad discretion over a variety of disposition or accountability options for misconduct. Options include administrative actions ranging from informal counseling, extra training, withdrawal or limitation of privileges, and administrative separations, to punitive options such as Article 15, UCMJ (which is non-judicial punishment by a commanding officer), and trial by court-martial.

The UCMJ defines behaviors that constitute sexually based crimes, which include a broader range of conduct than is generally considered “sexual assault” in civilian criminal statutes. Additionally, disposition of sexually based offenses is withheld to the first commander with special court-martial convening authority in the grade of O-6 (which is a Colonel in the Army and Air Force and a Commander in the Navy and Marines).

For additional information on military ranks see Military Culture: Core Competencies for Healthcare Professionals. The legal definitions of the various forms of sexual offenses are found in Articles 120 and 125 and listed in Appendix A of the UCMJ.

“Sexual contact” is defined as —

touching, or causing another person to touch, either directly or through the clothing, the genitalia, anus, groin, breast, inner thigh, or buttocks of any person, with an intent to abuse, humiliate, or degrade any person; or any touching, or causing another person to touch, either directly or through the clothing, any body part of any person, if done with an intent to arouse or gratify the sexual desire of any person. [371]

The UCMJ provides additional information.

Military sexual assault cannot be understood apart from military sexual harassment, as sexual harassment creates an environment in which sexual violence is more likely to occur. One study of women veterans who had experienced rape during military service found that 62.8 percent of victims had been raped by someone who had sexually harassed them. Female service members who reported working in hostile work environments or experiencing sexual harassment were more likely to experience rape. [372]

In contrast to sexual assault cases, sexual harassment complaints are handled by the Department of Defense Office of Diversity Management and Equal Opportunity. [373] The 10 U.S. Code § 1561 defines military sexual harassment as conduct fitting the following description:

In addition, 10 U.S. Code § 1561 requires commanding officers who receive sexual harassment complaints from those under their command to commence an investigation and forward the complaint to the next superior officer in the chain of command. [375]

When seeking to understand redress for sexual harassment and violence in the military, SART members should also know that, in addition to the UCMJ, the Office of the Secretary of Defense can establish policies, assign responsibilities, and delegate authority to the services through directives. Directives are broad policy documents and leave implementation discretion to the services. [376] DoD instructions may be more specific, containing implementation of directives or including overarching procedures. [377]

The way laws and protocols are implemented may vary between each branch. It is essential that SARTs who interact with different branches of the military (for instance, a SART located near an Army garrison and a naval base) develop local partnerships that ensure cross-training and collaboration between civilian organizations and each military installation.

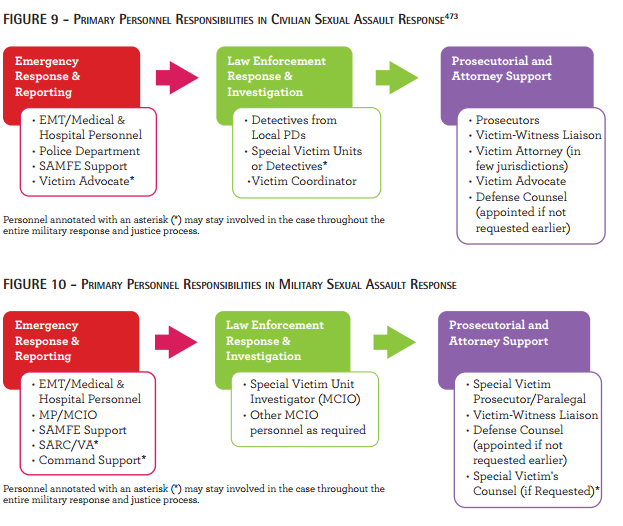

In most civilian jurisdictions, victims seek support for sexual assaults through hospitals, police agencies, or nonprofit organizations such as rape crisis centers. Federal, state, and local laws influence when disclosure triggers an official law enforcement investigation. In contrast, the DoD provides military victims two reporting options — restricted and unrestricted. Each option influences when a report triggers the official investigative process.

Restricted reporting —