The NSVRC collects information and resources to assist those working to prevent sexual violence and to improve resources, outreach and response strategies. This page lists resources on this website that have been developed by NSVRC staff.

- Diciembre 14, 2023

- Laura Palumbo

This series of six social media graphics is designed to guide you through talking to a friend about their problematic sexual behavior. This is the full length version of the We Can Talk About This Teaser. These graphics are a part of the Let's Talk set of resources for college students on talking with a friend about concerning sexual behavior.

- Diciembre 14, 2023

- Laura Palumbo

This series of three social media graphics is designed to prompt you to think about talking to a friend about their problematic sexual behavior. The teaser is a shortened version of the full-length We Can Talk About This. These graphics are a part of the Let's Talk set of resources for college students on talking with a friend about concerning sexual behavior.

- Diciembre 14, 2023

- Laura Palumbo

This series of five social media graphics guides you through how to respond if someone says you crossed a line. These graphics are a part of the Let's Talk set of resources for college students on talking with a friend about concerning sexual behavior.

- Diciembre 14, 2023

- Laura Palumbo

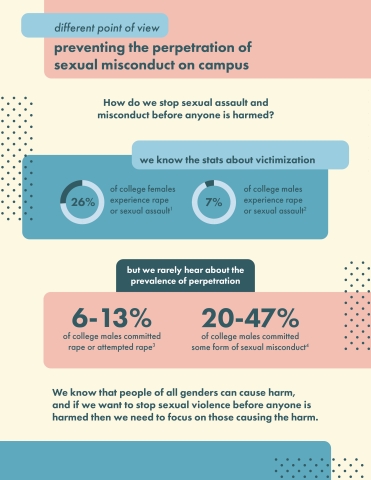

Learn facts and information about people who cause sexual harm and ways to prevent perpetration. This infographic is a part of the Let's Talk set of resources for college students on talking with a friend about concerning sexual behavior.

- Diciembre 14, 2023

- Laura Palumbo

This series of three social media graphics guides you through how to have hard coversations about problematic sexual behavior. These graphics are a part of the Let's Talk set of resources for college students on talking with a friend about concerning sexual behavior.

- Diciembre 12, 2023

- NSVRC

In this episode, Mo talks with Jess about the policy scorecard he created in partnership with the New Mexico Department of Health to help evaluate community-level prevention efforts. New Mexico Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs:

- Diciembre 04, 2023

- NSVRC

In this final episode of our Housing for Prevention series, Brittany Eltringham from NRCDV, Louie Marven from NSVRC, and Mo Lewis from NSVRC draw connections between the conversations in each of the three episodes and share their insights, highlighting the many ways prevention is linked to housing. This episode is part of a series on housing for prevention that we co-created with the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Show Notes: Homelessness & Adverse Childhood Experiences National Resource Center on Domestic Violence Safe Housing Partnerships

- Noviembre 27, 2023

- NSVRC

In this collaborative episode of our Housing for Prevention series, Janae Sargent and Ashleigh Klein-Jimenez from ValorUS talk with Gabby Boyle from the Sexual Trauma & Abuse Care Center in Lawrence, KS. This episode originally aired on July 27, 2023, on Valor's podcast channel PreventConnect, under the title "Housing Justice as Prevention." It was part of their series previewing workshops at the National Sexual Assault Conference. This episode is part of a series on housing for prevention that we co-created with the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Original

- Noviembre 21, 2023

- NSVRC

In this episode of our Housing for Prevention series, Caroline LaPorte and Gwendolyn Packard from the STTARS Indigenous Safe Housing Center talk with Melissa Brings Them about her work in the Native communities in South Minneapolis with those struggling with homelessness and addiction. This episode is part of a series on housing for prevention that we co-created with the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. STTARS Indigenous Safe Housing Center: https://www.niwrc.org/housing National Resource Center on Domestic Violence: https://nrcdv.org/

- Noviembre 14, 2023

- JL Heinze

In this episode of our Housing for Prevention series, Rebekah Moses with GBV Consulting talks with Mel Pasignajen about prevention lessons learned from working in the domestic violence, sexual violence, and HIV fields. This episode is part of a series on housing for prevention that we co-created with the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence. Show Notes Meeting Sexual Violence Survivor Needs in Transitional Housing: https://resourcesharingproject.org/resources/meeting-sexual-violence-survivor-needs-in-transitional-housing/ National Resource Center on Domestic Violence: https://nrcdv.

Paginación

- Página anterior

- Página 5

- Siguiente página